From the get-go, I'll admit that I haven't read the book from which Fight Club, the movie directed by David Fincher, was taken. I've heard some anecdotes about how the novel came to be, which are pretty dismissive of its message and worth. Not knowing the book, I can't speak about it, but from what I understand, the movie follows quite closely to the book's narrative. From here on out, when I mention Fight Club, I'll be referring to the film and not the novel.

As Latter-day Saints, we might be hesitant to consider such a film as Fight Club. It's form is admittedly crass and a bit too hype-driven for my tastes. But thematically it deals with issues that I find intrinsically linked to LDS perspectives and sensibilities.

The film opens with a dilemma. The group we're called to identify with and which gives us our starting point and groundwork for the film is a group of testicular cancer patients. The film's world is populated very literally and allegorically with de-masculinated males. The dilemma throughout the entire film is what should be done about this de-masculinization. The cause is unclear. On the one hand, as Meatloaf's character suggests, body building — striving towards the appearance of strength — has done the de-masculization. On the other hand, selfishness is to blame. One thing I'm glad to see is that the text avoids demonizing femininity and blaming it for the cause, as it would be so easy. There is of course the film's implied misogyny, but never does it assert that femininity is to blame. So whatever the cause, it is entrenched in the modernity and bourgeoisification of men, or as Tyler Durden states, a move away from the "hunter, gatherer" notion of masculinity.

I've written elsewhere on this site about Edward Albee's work and what he has to say about the ineffectualness of middle-class men and how that's led to the death of the American dream. I can't help but see similarities between the American dream, the 'rags-to-riches' story, and a Latter-day Saint journey to become more like our Father in Heaven. In a patriarchally-governed theocracy, we should be ever increasingly interested in sociological and psychological dilemmas that stand in the way of men becoming like their Father in Heaven. From my perspective, there are more and more families where the father is either absent or uninvolved, unable to lead or tyrannical. In the church, where the father's role as the head of the household is constantly reinforced and where the father's leadership in his home is a microcosm for all male leadership within the church, this seems to be a very fundamental theological dilemma. Likewise, our eternal goal, from an LDS perspective, seems to essentially have echoes of the American dream; a progression from the slothful natural man to the Christlike man "obtaining all that the Father hath" certainly has echoes of a progression from rags to riches.

Let me be clear here. My intent is not to profane King Benjamin's speech or our theology. Likewise it is not my goal to make any cultural ties to the gospel of Jesus Christ. I, too, am offended by the notion that our church is the "American church." Yet we might do well to acknowledge similarities between American cultural ideologies and ideologies within the gospel of Jesus Christ as told by Latter-day Saints. I say this mainly to suggest that when Arthur Miller and Edward Albee talk about the American dream, we should take interest from a theological as well as cultural perspective. It's in this framework that Fight Club becomes so fascinating to me.

Edward Norton's character, now a fragmented and de-masculinated, bourgeoisified man, describes for his counterpart, Tyler Durden, his efforts to overcome his state.

- His first attempt was to turn to pornography. This is mentioned only briefly, but a friend of mine pointed out that the remainder of the film's form follows suit and becomes pornographic. There is a CG sex scene where the sex is violence. This is a hot topic; the film gives little insight aside from suggesting that pornography is the first attempted remedy. Fascinating and tragic and horrifying and true. The following three attempted remedies for his de-masculinization are treated like abusive addictions, in the same vein that pornography is.

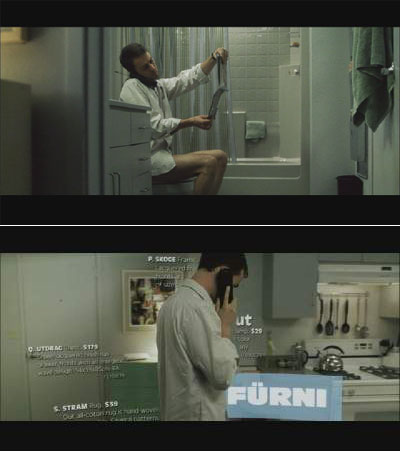

- The second attempt is materialism. Fincher exhibits his dazzling and satirical use of CG to associate glib materialism with pornography. Norton's character turns from smut companies to IKEA to fill his gender void. Several times his consumerism is described with phrases such as "It's what defines me as a person." I find it fascinating that this false bourgeoisie lifestyle is indicted for being unable to return one's masculinity. As though we weren't able to decipher the class references, the text is sure to point out that Norton's plates have "bubbles" to prove that they're made by blue-collar laborers, who are described as "honest, simple, hardworking" and "indigenous."

- The third method to regain masculinity is chemical dependency and pill-popping. The major scene describing this method has the doctor, despite Norton's requests for more drugs, prescribing "good, natural sleep," which leads to the most interesting method.

- 12-step programs, self-help groups, and new-age therapies of all kinds are implicated as not only failed remedies but as worsening the problem. In this framework, psychology is seen in terms of what it does to masculinity. The film's morality fascinates me in that my gut-reaction remedy to the loss of masculinity would be a "coming to terms with"/support oriented approach. It is these programs that are vilified as "touchy-feely" and therefore stepping further away from masculinity. Tyler Durden even goes so far as to say, "self-improvement is masturbation." In this light, self-improvement is self-destruction.

The second string to the solution the film presents is the destruction of consumerism: first by Norton's destruction of his material-laden condo and then a move to a decrepit and defunct, nearly condemned home devoid of materialism, and then finally the destruction of credit debt and by extension the idea of credit — a finance that cannot be touched. This second string is merely an extension of the first.

Far less time and clarity is sacrificed to these two solutions and by no means do I believe they could be described as literal suggestions for this very real dilemma. The suggestion is based in metanym and designed assuredly to be more of a provocation than a prophecy.

The film's misogyny

Tyler Durden says, "We are a generation of men being raised by women." He continues with, "I'm wondering if another woman is really the answer we need." Obviously a Latter-day Saint would differ here, on the one hand, as central to our doctrine is a committed and eternal heterosexual relationship. Yet on the other hand, I'm tempted to agree within this framework.

Once the fight club has started, the first major shift in the film illustrates what kind of femininity the film is discussing. Helena Bonham Carter calls Norton during a "cry-for-help" suicide attempt, the epitome of an emotionally needy/ 'high-maintenance' femininity. This passive aggression is placed in opposition to the violence, which is non-aggression. The masculinity-restoring violence also cures, in the end, this emotional manipulation and passive aggression. If this is what the film means by "needing another woman," then I must agree that passive aggression isn't the answer. But regardless, the film is shortsighted and misogynistic. In this world, the man is still the possessor and the woman the possessed, the man is the hunter and the woman is the hunted, sexually and otherwise.

No matter what aspect of femininity the film is attacking (or 'curing'), it is essentially misogynistic because it is the only portrait of women in the entire film (that they are reduced to being sick with emotional neediness and can only be 'cured' by a male sexual administration). This reduction has obvious negative implications and is in direct opposition to our view of temporalness as well as eternity.

This view of femininity also reveals the film's view of masculinity. The primary expression of the ideal post-modernity (as opposed to post-modern) male-male relationship is non-aggressive violence. Part of my goal here is to reassert that this violence should be viewed largely as a symbolic gesture toward something greater. The primary expression of the ideal post-modernity, male-female relationship is aggressive sex — suggested by the tongue-in-cheek rubber gloves and Helena Bonham Carter's falling off the bed in the background. The sex here, it is suggested, requires the male to be dominant and the female to be submissive to the degree that she falls off the bed.

Norton's character is only able to please Helena Bonham Carter (likewise a definition of what it means to 'be a man') when he becomes Tyler Durden, i.e. as a fractured, misogynistic man. Edward Norton's character can only become intimate with her on an emotional level, however, when he destroys the part of him which could please her sexually. Here, sexual pleasure and emotional commitment cannot coexist (that is, of course, unless Norton's character has absorbed Brad Pitt by this point, therefore allowing simultaneously for emotional commitment and sexual fulfillment. But my reading is that the film actually knows nothing about emotional commitment). The point is that the depiction of femininity reveals much about the film's assumptions about masculinity.

However crass they may be, the film also comes with references to Lorena Bobbitt. This reference has less to do with pop culture than with a long string of phallus references (Tyler Durden peeing in the food, splicing in images of male genitalia into children's films — as well as into our film, threats of neutering, not to mention countless crude gestures and phrases referencing the phallus), only this reference focuses on the woman as the aggressor. Here femininity is the cause of the demasculinization. The rest of the film doesn't express this point of view, but this reference furthers the misogyny as well as revealing its view of masculinity.

Pain/escapism

I've written before on this blog against escapism and how it seems in complete opposition to an LDS view of the purpose of mortality. (This, again, is one reason missionaries are not allowed contact with any non-canonical media.) So of course I take great interest when a movie of this commercial magnitude takes a stance against escapism.

I would say that the lye scene is the strongest argument against escapism that I know of. It is likewise the clearest illustrations in art of any philosophy that I know of. The form, both in movement and stillness, exhibits such precision and clarity that I am tempted to label it with complete harmony between form and content. We see through this dazzling piece of filmmaking, never gratuitous, just one example of why David Fincher has so many aficionados. The scene, then, suggests that a lye burn (the required branding that declares that that individual has overcome escapism) is a vital step on the personal path toward manhood. In other words, to be a "man," you must wholly reject escapism, facing your problems rather than running from them. Again, if nothing else, we might do well to discuss this scene or some remnant of it at our priesthood activities. That facing the pain required of us is intrinsically linked to manhood, or priesthood, if you like, especially when founded on the pattern of our Savior who "did not shrink," and drank the cup the Father gave to him, seems pretty right to me.

However, as the scene progresses, it reveals a temptation that comes with this great power once we shed escapism: to forsake God. Rather, the philosophy is that either there is no God, or that God has immense disdain for man, or that man is God. (I will refrain from drawing any parallels between an LDS world view and the last option, as that is far too complex and troublesome a topic for me). But this fragmentation, by definition, is agnosticism rather than atheism. Yet the dialogue should stand as a warning on all three fronts, that this pursuit of 'manhood' has contained in it some very twisted heresies if we are not vary. And more and more those ideas become a slippery slope.* While this perspective does allow for profound connection between our forefathers and our Heavenly Father, its outgrowth is perverse. It seems clear to me that whoever penned the question 'if our fathers gave up, what makes us think God didn't?' may be sincere (and it maybe a question worth asking), but that person doesn't know the God mentioned in the Gospel according to John, or the God mentioned by Joseph Smith. Though we can learn from the sentiment, we should never forget the truth we have obtained.

History/masculinity

Modernity, filled with place-lessness, alienation, and corporate dishonesty, has formed an image of masculinity that is rightfully questioned here. One scene shows Tyler Durden and Norton's character as they view advertisements for Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger on a bus. They view the men's bare bodies and remark that they "feel sorry for guys packed into a gym." The statement adds extra weight as they are both more fit than the men on the advertisement. The models' fitness is bourgeois. The goal of Norton's and Durden's fitness is much more primal and pragmatic/holistic. They are prepared to assert and defend while having a need and Maslow-esque purpose. It's this distinction between consumerism and masculinity as well as the film's unique view of violence as non-aggression that gives us the proper frame work to understand their view of male historical figures or the history of masculinity.

Tyler Durden and Norton's character ask each other back and forth who they would choose to fight. Answers of authority figures, such as "my boss" and "my father," have hints of a challenge, true, but come more out of a need for connection with these figures. The protagonists desire to fight them out of respect and not disdain because they are only known in a modern and therefore completely disconnected world. This violence is essentially about respect and connection. The film's mentality is that violence brings male unity. In this context, we understand more the desire to share this violence with figures such as Ernest Hemingway, Abraham Lincoln, and Mahatma Gandhi. All three figures are great minds and important leaders or artists, but the last gives us the greatest insight: Fight Club is just as much about the non-violence Gandhi championed as it is about broken noses.

Conclusions

There are obvious differences between an LDS world view and Fight Club's world view. Definitions of hedonism might be the biggest distinction. However it takes as its central topic masculinity (something LDS scholars have taken specific interest in. I believe that BYU professors are the most predominant if not the only writers for journals on men's studies in the United States.) Likewise, the film rejects pornography, consumerism, chemical dependency (though the protagonists still frequent bars), and 12-step programs, all of which in one way or another have made their way into modern definitions of manhood. This alone should cause Latter-day Saints to take note. However, it is what lies beyond the metaphor of violence that intrigues me most, that there is something in the relationship between men that, through modernity, we have lost. That the key to unlocking that secret element might be in the separation between violence and aggression does not seem so outlandish to me.

I wouldn't suggest watching the film as a priesthood quorum, but I do think that if the ideas and dilemmas as well as the possibility for solutions were digested by members of our priesthood quorums, I think that each of us might be more ready and able to function in our priesthood quorums. It does seem to me that we might be more service oriented as well as being more prepared to lead if we reconsider what it means to be a man.

Obviously, I don't agree, and we can't agree, wholeheartedly with the film's definition of what it means to be a man, and certainly there is no room in our families or in our church for the misogyny alluded to, but our definitions of both might do well to be challenged by these positions.

____

*Also worth noting is that in the film's vocabulary, the 12-step programs had replaced church. The film's protagonists are coming from a place where pop-psychology programs are the meetings which have replaced worship of God.

18 comments:

Trevor,

This post, to me, speaks to one of the great tragedies of our popular media. I find so much value in what you wrote.

I firmly believe, as I have stated before, that profound truth can come from any source, including a movie with no obvious redeeming value. The trouble lies in the discernment and the distilling.

I appreciate how sensitive you are to the value of the ideas you wrote about without claiming that the movie itself is "good" by their virtue. I find no inappropriateness with your suggestion that these ideas be discussed in a priesthood quorum - I applaud it. While agreeing with you that quorum viewing of the movie would be unsuitable, I endorse the idea that we as a people should extend our search for truth to include the works of those who do not share our faith, but have been blessed with gifts of knowledge and wisdom in other areas. We may have an exclusive claim to authority, but not to personal revelation or morality.

This is the tragedy I'm speaking of: that there are many people of great talent and inspiration whose works have beneficial, even edifying messages, but are inaccessible to Latter-day Saints because they come at such a high price in terms of intellectual and moral cleanliness. Their content is at odds with the commandment, "Let virtue garnish thy thoughts unceasingly."

Paradoxically, in this very commandment is the key to discovering their value without polluting our minds. The garnish of virtue enables us to discern and appreciate the good in an impure presentation while minimizing the impact of the bad. We can discover the truth in the Apocrypha, says the Doctrine and Covenants, by the spirit of discernment. Nevertheless, as President Benson is so often quoted as saying, "the mind through which this filth passes is never the same again."

The thing I want to say is that, like the Apocrypha, the translation of which was not needful, movies like Fight Club are not needful to be seen. However, the themes you have pulled out of the film are worthy of discussion and can enhance our understanding of truth. Their study, when carefully grounded in scripture, can improve our relationships with our Heavenly Father.

I want to say thanks for your discernment here and for making me think my ideas on this head through a little better. I'm glad you wrote this because, as much as I lament missing the art and the good of it, I will never see this movie.

Adam,

your comment has spurned some good thought in me and I've started a longer response to be posted later, but I wanted to say this: I think it's good to have these distinctions and without them we become lost. Your sharing of President Benson's quote is especially effective.

However, I'm unclear about some of your terms. I wonder what you mean when you say 'intellectual and moral cleanliness'? I might make my own guesses, but it seems safer to ask.

The film in question seems to transgress sacrament meeting behavior: there are more 'F' words than I would ever know what to do with. But I wonder if this is the behavior to which you are referring.

It, however, raises another question: where are we getting our information from which we draw our conclusions about what films to watch and what films not to watch? Is it solely because of the rating? Or are the trailers (very often something COMPLETELY different from the film) our only contact?

We do have a dilemma: How do we "Let virtue garnish [our] thoughts unceasingly," if we are trying to hear the voices that sometimes disagree what is virtuous?

The simplest answer doesn't mean its the most far off in my mind: We don't let virtue escape from our thoughts even when we are in situations where virtue is absent.

I believe the reading I've given of this film has been fair to the film and lead by discernment and the desire to find virtue rather than by fault-finding.

I'm not saying you need to view the film, though as a rule I think it would be a good idea for people interested in the priesthood to consider it. But I am saying that one side of the dilemma need not discount the other side of the dilemma.

curious as to your (everyone's) thoughts

Whereas I have never seen Fight Club, I can't say too much about it (though having read this post, I now know far more about it than I ever did before), but your discussion on manhood and manliness is very intriguing to me. There's a book one of my brothers gave to me that I've read bits and pieces of here and there called Wild at Heart: Discovering the Secrets of a Man's Soul. It's by a guy named John Eldridge. It was an interesting read (what I've read of it). The man has strong, Christian faith in God, but he talks a lot about how Christianity as a whole, or at least the way Christian religions have set themselves up, really kind of emasculate their men. He talks about God and Jesus in terms of manliness, pointing to the wildness of nature as an example, and talks about how manhood is slowly becoming extinct and replaced by cordiality, which is, for better or worse, most definitely the case.

One thing that really frustrates me about the current LDS cinema (particularly the videos made by the Church itself) is our portrayal of Jesus. The Man was a carpenter! And He was a pretty passionate fellow, too, overturning tables in the temple, calling the scribes and pharisees sons of the devil, talking about millstones being tied around people's necks--He really was that same Jehovah who sent down fire from heaven from time to time--the same Guy. Yet we always seem to portray Him as some kind of hippie, speaking in an airy monotone, knowing no wrath, having no fire, and with nary a callous on his hands. I imagine Jesus was the sort who spoke boldly and carried a big stick. And I imagine that, though He had no apparent beauty that man should Him adore, anyone who saw Him probably had reason to think, "Wow. He is all that is man." And I think that we who are in His Church, bearing His Priesthood, should strive to be a bit more like that.

Maybe I would like this Fight Club movie....

Trevor,

Thanks for the response. I agree with you that you've treated the film fairly and sought the good. That's the spirit of the 13th Article of Faith that's missing from so much of our judgment when it comes to media.

Your entire excellent treatment illustrates how different a film can be from how the trailers make it seem. Based on the trailers, I expected this film to be a trash dump with no redeeming value or attempt at any virtue beyond the "cool factor" and the presence of Brad Pitt. How differently I feel now.

As to my comment on "intellectual and moral cleanliness," I admit that I am not as satisfied with that language as I would like to be, but I was at the time of writing, as usual, somewhat pressed for time.

What I am referring to is the question of how a film impacts our thinking after we have seen it. Unwholesome images and thoughts can be sticky and remain a subtle influence long after we have stopped trying to despise them. I also am concerned about the idea of coming out of Babylon. If we partake in media because of its message, without much concern for what we have to wade through to get that message, are we really striving for a higher sphere?

I want you to understand that I'm not accusing you or anyone else of any of this, I just try to carry the caution in my mind.

As simplistic as it may sound, my reason for never seeing the movie is the rating. Pure and simple. I cannot separate myself from that standard because the Prophet has spoken it. President Eyring's message in the Ensign this month only confirms to me the importance of following prophetic counsel even if only given once. I've written much more about the "R" standard on my blog under "Rantings and Ratings," although I'm afraid my tone there was a little more frustrated than I now care for.

Also, you nailed my thought on how virtue helps us discern. It is to be a garnish, not every dish on the buffet. One is forced to ask the question, "Does God ever think about anything unvirtuous?"

I won't try to answer that now, but I will say that we all have to deal with hard issues and uncomfortable topics from time to time. Confronting evil without allowing it a proper place in our thoughts seems like an interesting proposition. However, Christ overcame temptations by giving them no heed.

I'm out of time, but I hope this gives you what you need to understand my comment and continue this discussion.

Thanks,

Adam

Schmetterling,

Thanks for the heads up on the Eldridge book. Sounds really interesting. One similar book you might find interesting is a book called 'Iron John' by Robert Bly. It likewise calls for a return to Nature and Masculinity. Its premise, (though it's non-fiction) is taken from a Brothers Grimm story. When it came out, I guess it caused quite an uproar in some circles. For what it's worth.

As for this: "The Man was a carpenter! And He was a pretty passionate fellow, too, overturning tables in the temple, calling the scribes and pharisees sons of the devil, talking about millstones being tied around people's necks"

I can't believe how much I liked what you wrote. Really thought provoking. I don't know that we agree how His portrayal should be varied, but I think we agree that it should be. I don't think that the majority of psychoses existed then that do now (I think modernity is at the root of bi-polarity), so I don't think that his passion would be expressed the way we express ours. So when I read that He was a carpenter, I'm reminded that there was a lot of depth to this man. However all we get are Greg Olsen paintings of models. You're right that that's wrong, I think.

I had a professor once (a very sensitive, thoughtful, quiet woman) who stood in front of class talking about a Greg Olsen-lead/typified movement to describe the Savior as a 'pretty-boy' Model who was always in pastels and soft focus. She began to shake as she wept and said "I cannot tell you all how evil this is..." and continued to repeat that it was evil as she tried to compose herself. That really did a number on me, because I trusted that she knew more about the Savior than she let on. I think she had had a very difficult life and had come very close to Him. It just has stuck with me.

Adam,

I didn't mean to make you feel defensive about not wanting to see R-rated movies. We of course don't want to get pharasitical (I would define this term as being to blinded by the law to see the salvation of Christ) in any regard, but, as President Packer reminds us, it's always better to err on the side of being too far from the edge than too close to it. President Hinckley only said once what he said about one piercing in each ear at the most. I was in that meeting, and I'm glad I was able to hear the counsel of the prophet and see the effect that it's had on the church since then.

I believe that the context, implications, meaning, and audience of that statement about R-rated movies to be quite different from President Hinckley's counsel. We are free to disagree here, and I hope we do disagree here; my goal is not to convince you.

For what it's worth, I will say that I have a friend who said he felt prompted to take his teenage daughter to an R-rated movie. He felt she specifically needed what was in this film because of some hard times she was going through with the church. I know I've been counseled to seek out certain movies and to avoid many others. I guess what I'm trying to say is that following the Spirit can never lead you astray, and if the Spirit confirms to you that decision, then don't ever betray what the Spirit tells you.

Funny you mention Elder Eyring's talk because I remember being especially struck as he told us that things that are especially important are repeated over and over. They are repeated several times in each conference. I wrote most of my thoughts about it on Thinking in a Marrow Bone, and I'll write more about it here, but I think there are many reasons that the church's stance has changed.

Trevor,

Did I seem defensive? I didn't mean to. I certainly didn't feel that way either when I read your reply to my first comment or when I wrote my response.

I have a tendency to come off a bit more sour than I intend. I thought that might be just in person, but apparrently not. : )

Please read all my comments with a friendly tone of voice.

I certainly got what you did from President Eyring, but the thing that struck me the most was the idea that any counsel should be followed while repeated counsel should "rivet our attention." He said that each time we ignore prophetic counsel, we become less sensitive to the spirit. To me, this suggests looking for repetition, but not waiting for it.

I'm not sure the Church's stance has changed, but I think the phraseology has been altered in order to, among other things, avoid letting the MPAA interpret God's laws. I don't think the ratings standards quite meet the "unchanging" criterion that the word of God is held to.

My position is that, while great benefit can be gotten from movies, in most cases the same benefit can be obtained in other ways. This makes a film one of several appropriate tools for the job, which in turn provides options. If the wrench is rusty, use the ratchet. Also, it helps avoid the social obligation (seemingly so easily created) to keep up with current movies. As if that were the pinnacle of social involvement.

One of my heroes is my second mission president. In his very first address to the missionaries he taught me something about rules that I'll never forget. Namely, that while almost all come with exceptions, those exceptions are not written into the rule. They don't need to be because they are few and obvious. Otherwise, they become the rule.

I think you named the one thing that can dictate an exception to any rule, and that is the guidance of the Spirit. I believe what you said about being prompted to see R rated movies. While I would struggle with that, I hope the Spirit could convince me. Nephi took a much greater risk on a prompting - repeated, incidentally.

My first mission president set the standard for me there when he rented an entire theater (not just one screen), gathered the whole mission, and showed us Remember the Titans after taking his teenage daughter to see it. Like you said, he felt that the mission needed what was in that film, and it turned out that it did.

My mind is a fenced city. Far from being pharisaical, I try to think of the R standard as the baseline that the apostles have talked about. I start there with a movie, and see if I can determine how high a bar it clears before I decide to let it into my brain. It's possible for other virtues to outweigh the rating, but it's rare, very rare.

I've considered seeing a few "R's" because I thought the virtue they seemed to contain might make it worth it. It's hard to tell in advance.

As I've never identified a prompting to see a movie I've had doubts about, however, I've always chosen to follow another of my rules that you've correctly identified, which is to err on the side of caution.

Trevor,

I appreciated this post. There is some very perceptive ideas in here. I am glad to be able to read them.

Trevor,

I have two points to make here, so please bear with me.

First, I wanted to say that I took the time to read some of the material you've written elsewhere about ratings. I never intended for my original comment to lead to a discussion about ratings, but here we are.

I have to admit with no small amount of embarrassment that I had not thought of the R standard in terms of the worldwide church. I'm not saying you've completely changed my mind (I know you're not trying to), but I am starting to agree with you that ratings in general should not be a part of how we determine whether to see a movie.

This actually isn't too far from where I previously stood, which is why I can write this with so little internal conflict. It's been a long time since I've used any rating but R as a deciding factor. I've often made the same argument you made about the vacillating nature of MPAA standards as a reason to move to a positive rubric instead of a system based on what a movie doesn't have. I've just always held that R was a point of no return. I can see the hypocrisy in that now.

I don't agree with you about the context of President Benson's famous counsel, but the reasons for that are not best suited to this thread.

I just wanted to say that I'm thinking about this and thanks for the insight.

Now, because I realize that my first comment probably distracted this entire thread from your original intent, let me say something about the body of your excellent treatment of Fight Club.

I'm glad that you made the distinction, as the film apparently does, between musculature and strength. This may be a childish example, but I've seen many cartoons in which the physically strong, musclebound men have the most feminine personalities. It's a common comic device, but I think it's so effective because there's an element of truth to it. The iconic narcissistic bodybuilder is about appearance, and when it comes down to it, he's usually the weakest one on screen. As the prophets have recently said, the gospel is about becoming, not appearing. Elder Carlos Asay gave a General Conference talk about true manhood in 1992 that would make a good reference here. I also seem to remember a talk about a "Priesthood Man," but I can't seem to find it. Does anyone else remember this?

I also found the reference to Ghandi fascinating. Brad Miner's book, The Compleat Gentleman gives an interesting anecdote.

He tells the story of his young son's elementary school teacher who called him in because his son hit another child in self defense. The teacher was appalled that Miner found nothing wrong with this. He said that he would encourage that behavior in boys, (here I'm paraphrasing) "unless you want to turn them all into little Ghandis." The teacher was aghast that he didn't want to. His reply was that he wanted his sons to be "little Gallahads."

There's much I don't agree with in the book, especially the implied incompatibility of non-aggression and self defense. I wonder how the Nephite approach, "Inasmuch as ye are not guilty of the first offense, neither the second, ye shall not suffer yourselves to be slain by the hands of your enemies" (Alma 43:46) would be received by the two characters mentioned above.

What are your thoughts?

I see no women have joined in the conversation. :)

As for this [Schmetterling wrote]: "The Man was a carpenter! And He was a pretty passionate fellow, too, overturning tables in the temple, calling the scribes and pharisees sons of the devil, talking about millstones being tied around people's necks"

[Trevor wrote]: I can't believe how much I liked what you wrote.

It resounded with me, too, since I get very impatient with His portrayal as...what was it?...hippie something. Yes! I remember that He was a carpenter; yes! I remember that He cleared the money changers out of the temple; yes! I remember His passionate defenses.

I have always thought He must have been charismatic, an orator of great strength (and, oh look here again, passion).

[Allow me to digress and plug Dogma as one of the most faith-inspiring movies I've ever seen.]

Anyhoo. About the emasculation of the male.

I don't like watching this happen and I haven't for a while. It does no favors to women to have no concrete role models of masculinity to hold onto.

I haven't seen Fight Club (yet--it's one of those things I just haven't gotten around to since, oh, '99), but what I saw in the trailers was the re-masculization of men and I like to see/read stories like that.

Thank you for this. I'll be keeping up with this blog now that I've found it.

I thank everyone for the comments (especially Jeff, a good friend, who it's always good to see).

Next, Adam: we'll continue the standards discussion on the standards post.

This concept of "muscular" characters with high pitched voices has quite a history doesn't it? That will require more thought.

But I definitely think both 'Gallahad' and Gandhi are to simple of role models for all boys. There's no nobility in nameless cloning.

But I will say that Gandhi seems endlessly more complex than Gallahad. If the implication is that Gandhi was not chivalrous, or courageous, or bold, I think there is something seriously slanted going on there. I think Gandhi's progression from erudite to his more humble, self-sacrificing endings could be read as a return to manhood.

He was no Jeremiah Johnson, But I think of Thoreau as very much as being a man (though I don't want to promote his as an icon of absentee Fatherism [I don't know if he even had a family, but much of Manhood for me is tied to fatherhood and Husbandhood]).

MoJo,

How right you are that no women had jointed the discussion as of yet (and I certainly hope more do). I thank you for you comment, though I secretly admit frustration at your experience with Dogma. My stance has been (and not seeing it after a track record of complete disapproval of every other Kevin Smith effort I suffered through) that no one I know has had a positive experience seeing it. While I'm not planning on seeing it anytime soon (there are hundreds of Japanese movies I'd hope to get to first) I'll say your comment may work on me in the years to come.

I think Miner's point in telling the Gallahad v. Ghandi story was to illustrate that children, especially boys, are sometimes taught not to stand up and defend anything. His entire book has that Arthurian sort of defense-of-the-crown/questing feel to it.

I think a better lesson to draw from that story is what I might call the Abinadi paradox: that of courageous defense vs. turning the other cheek. Maybe the "Ammonites v. Moroni Paradox" is a better title. I'll mention that again under paradoxes, but it seems applicable to manhood as well.

I think Miner's point in telling the Gallahad v. Ghandi story was to illustrate that children, especially boys, are sometimes taught not to stand up and defend anything. His entire book has that Arthurian sort of defense-of-the-crown/questing feel to it.

I think a better lesson to draw from that story is what I might call the Abinadi paradox: that of courageous defense vs. turning the other cheek. Maybe the "Ammonites v. Moroni Paradox" is a better title. I'll mention that again under paradoxes, but it seems applicable to manhood as well.

I thank you for you comment, though I secretly admit frustration at your experience with Dogma.

Let me qualify that by saying I like bizarre stuff and find weird themes and leitmotifs no one else does.

I mean, really. I like Pedro Almodovar and Quentin Tarantino and Baz Luhrmann, too, so we just may be coming from opposite aesthetics. I will admit I found Chasing Amy unwatchable, but Dogma was NOT in the realm of Clerks et al.

Two questions:

1. What's the film where you were advised to have been married for 3 years before you watched it?

and

2. How do you know what you will and won't watch if you're not expressly told through prayer OR are you told through prayer for every movie? (No snark intended.)

children, especially boys, are sometimes taught not to stand up and defend anything.

Adam, this is right on the money, IMO.

To paraphrase an old saw, the bullies get bulliers and the bullied get more bullied. The current educational trend of across-the-board-and-equal punishment for children (esp boys) engaged in a playground scuffle hurts more than helps.

MoJo

I'll admit to being taken away in Almodovar's films, though I really have to be on my toes to stay... unfettered but his pull. "Lab coat and Goggles." So thats a rarity, but quite wonderful.

I find Moulin Rouge crass beyond crass (formally mainly), but some people I really respect love his movies.

about your two questions: I'll email you the answer to the first, but I just decided not to post it.

towardanldscinema at gmail dot com

2. NO, I don't pray about every movie. But sometimes guidelines come. Its very rare that answers or impressions (meaning things not asked for) come in specifics like titles or whatnot. I rarely even ask about certain things. Mainly I will have a title come in my head and get an impression outside of prayer and later I'll pray about it, trying to open my mind or heart for and answer, and I'll feel whether its good or not right then for me. However a lot of the time I just get nothing (either I'm not ready/worthy or God doesn't want to answer in that way right then). That is when I decide to just wait and I don't make a decision until later.

I read a lot about what others have written. I should say that content sites offer help to me, but I can't say that I've been more than a few times.

Most of the time I usually know enough about the filmmaker's work or sensibilities to know what I'm getting into. I'll admit that I have been surprised (much to my dismay) but that is rare. I search on sites that I've included on the sidebar and usually get the answers I'm looking for. That or I ask friends who've seen it.

But I always try to get several sources before I try something really new.

The biggest thing is to know yourself at that moment, what you're ready for and what you're not.

Trevor, I've read your article twice now, and I have neither read the book, FIGHT CLUB, nor seen the movie, but I have been given to understand (SPOILER WARNING, if necessary) that Brad Pitt plays Edward Norton's "alter ego" or "shadow" (in the Jungian sense) or maybe even his "natural man?" and before I read your article, I wondered if you were going to say that you saw aspects in the story about overcoming the natural man.

Now that I've read and reread your article, however, I see that it is not about that, though I'd be curious to know if that aproach is even a possibility in the interpretation of the story.

The thing is, I'm not entirely clear on what you are saying in this article, even though I've read it twice.

Non-aggressive violence is how men should relate to each other? And emotional commitment (along with sexual violence?) is how men should relate to women, and Norton's character might be able to achieve this by accepting his "shadow" instead of resisting it?

Having read other articles in your blog, I am sure I've misunderstood you.

I do see some connection between the non-aggressive violence and the rejection of escapism in the idea that a man engages in a fight to face things, to "take it like a man," instead of avoiding them, but is it truly emasculating to ask a man to find a mental (as in out-smarting) way of dealing with whatever it is he is supposed to "take" as opposed to a physical way?

Anyway, I guess my response to your article is to try to tell you how I didn't "get" what you were saying. Your "conclusion" did not seem all that conclusive to me, and I did not really see what specific points from the movie (other than the list of things that don't work) would be of interest for a priesthood quorum to discuss. I guess that went right over my head. (shrug)

Kathleen,

How thoughtful your response (and how brave, I might add, to weed out my lack of clarity). Here we go:

(I'll save the natural man discussion until I've had more of a chance to digest it... but the prospect is intriguing.)

1. "Non-aggressive violence is how men should relate to each other?"

I think that the word 'should' is stronger than I would use. I think the non-aggressive violence is a metaphor for something missing from male-male relations, something rooted in physicality, strength, and directness, while eschewing both navel-gazing and aggression. Now, the word 'should' becomes troublesome, because I feel that I am a better person for having contemplated these things, and my ability to enhance my 'masculinity' will be aided by these thought processes and the framing of these ideas. But I don't think that my conclusions are prescriptive. The only 'should' I see right now, is to continue to consider and confront these ideas.

2. "And emotional commitment (along with sexual violence?) is how men should relate to women, and Norton's character might be able to achieve this by accepting his "shadow" instead of resisting it?"

And here's where I realize my fault in approaching this article. I wrote it, in effect, to encourage Latter-day Saints to take interest, however I wrote it from a place assuming that my audience would have already seen it (I, for instance didn't even include anything specific enough to be really considered a 'spoiler.') I also don't really watch movies in terms of plot much either, so when I write about them I don't really outline the (much needed) plot description.

I'm assuming that we're all coming from a place where sexual violence, or violence in general (especially toward women) is an abomination. Though I do admire the ability to absorb and withstand violence (I think I'd be a better person, honestly, if I where 'tough enough' to get beat up on a regular basis). My lone use of the word 'misogyny,' I had hoped, would suggest my view of that. A major tenet of LDS ideology is the respect of women, as well as a view of sexual intimacy as a unifying act rather than a violent, and therefore fragmenting act. If something unifies us, it is holy, if it fragments us, it is evil.

As far as the film goes, the plot (in perhaps the most completely absurd—meaning anti-realistic— conceit) has Edward Norton's character inflicting aggressive violence on himself in order to kill Tyler Durden's character. The process, as I see it, is: 1.Edward Norton becomes fragmented to create his 'non-aggressive violence' club, 2.Edward becomes like his 'shadow' 3.Edward Kills his 'shadow.'

First appropriation, then annihilation of the alter-ego. The difference in step (2.) is that Edward retained (or perhaps gained) the ability for emotional commitment to women, where as Tyler (as well as the Edward-Tyler complex) was incapable of emotional intimacy.

I wrote that I see the film as misogynistic and therefore incompatible with LDS theology (most recently displayed by the Feb. Training Meeting). However, the protagonist does strive for emotional commitment in the end. The biggest difference is that the film's philosophy does not have the tools necessary to accomplish or account for emotional commitment. But this shouldn't completely discount what new tools the film does have.

3."is it truly emasculating to ask a man to find a mental (as in out-smarting) way of dealing with whatever it is he is supposed to "take" as opposed to a physical way?"

Again, I do see the violence as a metaphor, but I don't think this is the point. At least part of the problem is this disconnect from the body. The modernity being discussed here has us experience everything vicariously (through film, literature, the internet) but to such a degree that we have lost touch with physical experience. As I see it, a major part of our goal on earth is to obtain and learn how to use our bodies in a divine manner. For the most part, I believe that we all would be more spiritually mature and developed if we lived on farms and worked with our hands for a living.

Now, I remember that as a teenager I would break glass bottles against alley walls if I found them. While there was some kind of release, that violence was still centered in aggression and destruction (i.e. I fight because I'm angry and I want to destroy). Fight Club's violence isn't rooted in construction, but it is non-aggressive (i.e. I fight because I'm a man, not because I'm angry).

Your question suggests that there is something 'to deal with.' The only thing to 'deal with' in the movie is modernity. This 'disconnect' from the body is the thing being fought against, so to prescribe a mental process for the malaise of too many mental processes is counter-productive and actually adding to the problem. I don't know how I could have expressed this more clearly in the article (which doesn't mean someone else couldn't have done a better job).

4."Anyway, I guess my response to your article is to try to tell you how I didn't "get" what you were saying. Your "conclusion" did not seem all that conclusive to me, and I did not really see what specific points from the movie (other than the list of things that don't work) would be of interest for a priesthood quorum to discuss. I guess that went right over my head. (shrug)."

I hope that what I've written here clarified my positions and my reading of the film a bit, though I doubt it has done so completely. I believe that the malaise addressed in the film affects modern masculinity and the film frames these problems in a fresh, profound way. I will clarify that I don't think my article should be read in priesthood quorums, but the films topics are at the root of what I see as the disintegration of the home. Fatherhood, priesthood, and masculinity are all under attack, and this narrative places those attacks in a light (as well as posing a metaphorical solution) which allows for greater understanding and smarter defenses.

I'm of course sad that my framing didn't make sense to you, but though I realize this was my best, most thorough shot, I also understand that it won't resonate with everyone. I'm glad you told me that it didn't with you.

Okay, this definitely helps, Trevor. Thank you.

I'd like to point out that you used the word "should" first (grin). Notice your title?

So, moving to your point #2: if Edward's "shadow" was his "natural man," then the film showed him "overcoming" it? It sounds that way to me from what you've said about Edward retaining or gaining the ability to have an emotional commitment to women. I may try to see this movie after all.

Thank you for your third point. Constructive physicality, working with the hands, working with the soil--yes, that makes sense. I'd like to add, hiking, rock climbing and rappelling, mountain biking, and other risk-taking adventures that pit someone against nature in a non-aggressive way. Maybe that's why scouting includes camping and hiking and other such physical activities? Developing the whole soul, not just the mind, but the body as well.

I have to confess that I can relate to the bottle breaking to some extent. For me, crunching fallen leaves is very "therapeutic," probably in much the same way, though while that could be considered assisting in the natural breaking down of elements, I would not break bottles because I would worry that the broken glass might hurt someone or something later on, and the crunched leaves are not so likely to cause injury.

As for there being something to "deal with," if there is something to "escape," then there must, by definition be something to "deal with" whether it is what the movie presents or just what life (modern life?) presents. And "being a man" means you can "take it," whatever "it" may be?

I am intrigued by the idea that someone would "honor" another by fighting with him, implying, I guess, that the honor comes from the knowledge that the other "can take it?" From what I have observed, fighting seems to be more of a testing activity, a way of finding out if someone deserves honor by seeing if they CAN "take it." Is it both or only one way, or neither? And not just fighting, but competition in general?

I'm fully in favor of cooperative physical endeavors, and while I can understand competitive physical endeavors, I guess I don't like the me that I tend to become when I allow myself to get competitive, so I lean more toward finding ways to cooperate (the non-zero-sum stuff).

I've played board and card games with my husband and his family, and I've gone hiking and rappelling with him and his friends, and so on. But the work I have done with him in fixing things around the house (we are both "handy" in overlapping ways and so make a good team) is what I cherish most. And I'm happy to let him go off on his hikes, especially now that I have read and better understood your points. I hope that this kind of physicality is working for him in the ways that you have discussed are needed for men in this modern world.

Post a Comment